Like a competent driver, the sensible person must be aware of their surroundings and the events occurring therein in order to avoid catastrophe. The same applies when observing developments across the political spectrum. The speed of those events is a variable beyond the control of the driver. But from the perspective of the astute observer it’s possible to ascertain what has occurred, what is occurring and what will likely occur as a result of past and current trends.

One of the more interesting developments in recent times and certainly the most colourful is the growing influence of the far-right in mainstream politics. Through a combination of brand advertising, sloganizing, boorish behaviour and corporate sponsorship the Extreme Right is making its presence felt across the world. Some on the so-called “Alt-Right” have claimed that their brand of conservatism represents the new counter-culture. Indeed, charlatans such as the White Supremacist Richard Spencer and Milo Yiannopoulos have made in-roads into popular culture by tapping into the grievances of disenchanted millennials (see Victimhood Part 1.

It would be simplistic to declaim such unpleasant individuals and their followers as stupid or misguided but it would be equally unwise to credit either Spencer or Yiannopoulos with wisdom or intelligence. Though posing as leaders in the Alt-Right, neither of these men nor their ideas are the driving force behind the movement. The financial sponsors of the movement are wealthy interest groups including the Mercer family. Rather than being leaders, Spencer and Yiannopoulos are mere hand-servants.

The Extreme Right has always existed and its virulence in North America is owed to a combination of geography and religious and philosophical leanings at the core of Western colonization on the continent. Since World War II the Extreme Right’s move towards the mainstream of politics is the logical result of nearly fifty years of corporatist maneuvering. There is and was no central conspiracy at work to shift the political Centre to the Right. Instead various interest groups each armed with a shared sense of socioeconomic determinism hijacked the moderate political parties in most jurisdictions.

The first political grouping in North America to succumb to these political parasites was the traditional conservative movement. Whereas traditional conservatives stressed the importance of limited government, separation of church and state and fiscal prudence, traditional conservatism quickly fell under the sway of both Christian conservatives and neo-conservatives. The former Republican Presidential candidate Barry Goldwater (ironically much feted today by neo-conservatives) warned:

“Mark my word, if and when these preachers get control of the [Republican] party, and they’re sure trying to do so, it’s going to be a terrible damn problem. Frankly, these people frighten me. Politics and governing demand compromise. But these Christians believe they are acting in the name of God, so they can’t and won’t compromise. I know, I’ve tried to deal with them.”

Christian Conservatives were only one force that would transform North American conservatism. Christian conservatism is not a monolithic force and is far more complex than it appears. Like the political spectrum, Christian Conservatism has many aspects. Many right-wing libertarians also adhere to fundamentalist Christian teachings. During the Obama Administration, these and other groups coalesced around the Tea Party.

However, even within American Christian fundamentalism, there exists ideological difference between evangelicals, Catholics and Dominionists. All these groups share to varying degrees a sense of determinism on a range of issues varying from social and foreign policy to economic determinism. Of these, the Dominionists are arguably the most extreme in their views and as a result have generated greater links to the Racist Right. Those links are also complex.

For example, the Cosmotheist Church founded by William Luther Pierce derived its membership from evangelical White Supremacists. Pierce was the author of The Turner Diaries, considered to be a “bible” for the racist right. Pierce described Cosmotheism’s core principle as:

“…the purpose of mankind and the purpose of every other part of creation, is the creator’s purpose, that this purpose is the never-ending ascent of the path of creation, the path of life symbolized by our life rune, that you understand that this path leads ever upward toward the creator’s self-realization, and that the destiny of those who follow this path is godhood.”

Key to realising this godhood was advancing the white race to a position of “superhuman” status, a position that could not be achieved through the mixing of races. By the time Pierce founded the Cosmotheist Church he had already preached his racist vision of social Darwinism in his novel The Turner Diaries. In that distasteful book he envisaged a future race war in which fifty million white survivors would inherit the Earth. Pierce also promoted a strain of Edmund Spencer’s idea of “survival of the fittest.” Competition between individuals and races was, in Pierce’s view key to the betterment of mankind.

Dominionist Christian thinking, itself a branch of Christian Reconstructionism shares much in common with Pierce’s vision but with less overt emphasis on a race war. Dominionist theology argues that the world should be brought under Christian dominion and that all other faiths should be subordinated or destroyed. Reconstructionists occupied high ranking posts during the Administration of George W Bush. They included the Defence Department’s Inspector General Joseph Schmitz. Schmitz maintains close ties with Blackwater Worldwide founder Erik Prince. During the Second Iraq War, Schmitz described Blackwater mercenaries as his “Von Steubens (after the Prussian officer and founder of the Continental Army)” bringing Christianity to the Middle East.

A vision of apocalyptic destiny also sits at the heart of Dispensationalist Christian belief. Dispensationalists believe that the Messiah will vanquish the Anti-Christ at Armageddon in the state of Israel. Afterwards, according to Dispensationalist prophecy, the world will begin anew, clean of pollution and evil and life will abound.

Such mystical thinking isn’t far removed from the racist fantasies of White Supremacists such as Pierce. Furthermore on social policy, Christian Conservatism as a whole leans heavily towards a social Darwinist perspective of competition. At the same time that William Luther Pierce was promoting his intolerant, tax-dodging religious sect, the Christian Reconstructionist David Harold Chilton was arguing against social welfare programmes, culminating in his influential 1981 book Productive Christians in an Age of Guilt-Manipulators: A Biblical Response to Ronald J. Sider.

But Christian Conservatives weren’t the only force hijacking traditional conservativism. The neo-conservative movement gained influence at the start of the 1970’s through the Chicago School of Economics. Lack of adherence to Christianity is no barrier for neo-conservative thinking. Many of its most ardent promoters included the money grubbing former Assistant Secretary of Defence Richard Perle and Paul Wolfowitz, both whom are of Jewish descent. William Kristol, the editor of the neo-conservative Weekly Standard remains an intellectual force behind the promotion of neo-conservatism.

But what is neo-conservativism and why does it have such a cozy relationship with the Christian Right?

The practical and philosophical underpinnings are coinciding (if not for identical reasons) interests in maintaining the state of Israel, armaments spending and the desire for competition in the society at large. The Canadian philosopher John Ralston Saul sees parallels between neo-conservatives and Marxists:

“It is not unreasonable to place them among the last true Marxists, since they believe in the inevitability of class warfare, which they are certain they can win by provoking it while they have power.”

Bizarrely, it is White Supremacists who have in turn accused historic figures such as Abraham Lincoln of being Marxist for freeing the slaves. Also on an ironic note, Pierce, Perle and the Christian Reconstructionist David Harold Chilton professed strong opposition to Communism throughout their careers. Pierce was a member of the John Birch Society prior to joining George Rockwell’s American Nazi Party. Yet each of these men encouraged ideological, class and racial conflict.

It is yet another irony that White Supremacy itself is less concerned with conflict and more about stability, control and subjugation. By far the most astute analysis of the underpinnings of White Supremacist philosophy can be found in the sociological school of Socialist Feminist theory. James W Messerschmidt, one of the principle thinkers behind the theory posited the argument that White Supremacy is not merely concerned with race but with gender roles. The desired social structure of the white supremacist is one where white men dominate the community and where white women are subordinate to white men. White Supremacist thought adheres to a notion that women are unable to control their sexuality and that is a moral imperative of white men to ensure that women do not engage in sexual congress with anyone outside the white race.

Similarly, according to Messerschmidt’s analysis, black men and women are equally incapable of controlling their sexuality and therefore the segregation of the races is in part motivated by a need to control the sexuality of white women and black men as a moral imperative.

It may seem like a far cry between the racist and sexist views of White Supremacists and contemporary social conservatism until we recall the ongoing debate over abortion and healthcare in the United States, and in particular conservative attacks on Planned Parenthood in the US and public health care in Canada. In the kind of capitalist free market society promoted by modern day conservatives, women are therefore good for nothing but breeding.

Small wonder then, that Donald Trump’s comments about “grabbing her by the pussy” were not a liability among his supporters, nor too, the equally idiotic comments of former House of Representatives member Todd Akin when he described the female body as an “incubator.”

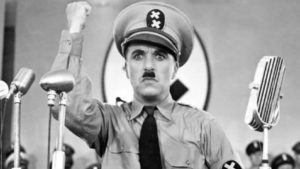

Dehumanizing people being a specialty of modern conservative thought, it is small wonder that many libertarians and conservatives are also techno-utopians. Peter Thiel, the libertarian founder of PayPal and who sat on Trump’s transition team is among many right-wing thinkers who believe that technology should be allowed to advance without regard to human interference. Thiel and others like him have apparently forgotten what World War II was fought over. While most tend to see World War II as a conflict between democracy and authoritarianism it was also a war against the dictatorship of technology versus the rights of the individual. Hence in popular entertainment Charlie Chaplin’s famous speech from the Great Dictator:

“Machinery that gives abundance has left us in want. Our knowledge has made us cynical. Our cleverness, hard and unkind. We think too much and feel too little. More than machinery we need humanity. More than cleverness we need kindness and gentleness. Without these qualities, life will be violent and all will be lost….

And:

“Soldiers! don’t give yourselves to brutes – men who despise you – enslave you – who regiment your lives – tell you what to do – what to think and what to feel! Who drill you – diet you – treat you like cattle, use you as cannon fodder. Don’t give yourselves to these unnatural men – machine men with machine minds and machine hearts! You are not machines! You are not cattle! You are men!”

Or consider Charles De Gaulle’s 1941 lecture at Oxford where he discussed the threat of technology to the individual:

{The only way out is for]”…society to preserve liberty, security and the dignity of man. There is no other way to assure the victory of spirit over matter.”

As with the Herbert Walker Bush and Brown Brothers Harriman during World War II, Thiel appears to be on the side of the Nazis when it comes to technological determinism.

Thus weighing all the above, it is easy to see how disparate elements of the Right could coalesce around a phony heroic and intolerant figure such as Donald Trump. Individual bravado may have played a role in putting Trump in the White House. However Trump’s presidency is a culmination of decades of disparate efforts by White Nationalists, Christian Conservatives and neo-conservatives to shape society into an ideological, social and racial warzone.

By and large, their efforts have not been in vain. Their opponents in the centre and on the left have fallen into several pitfalls. First, the centre has over recent decades parroted many neo-conservative talking points about “free” markets and competition. In turn liberal governments under Clinton, Tony Blair and Jean Chretien have embraced the twin mantras of demonizing the poor and privatizing public resources.

The Left has in turn moved to the centre-right. The Socialist Party in France held the same anti-LBGTQ stance as the Gaullists for decades. Francois Hollande proved to be no friend of the working class during his time in office, using State of Emergency legislation to crack down on unions and organised labour.

Canada’s NDP in a bid to appear more “palatable” to the electorate i.e. donors, has also moved to the centre. At both a federal and provincial level, NDP policy does not differ radically from that of the Liberal Party of Canada.

On the far left, both the anarchists and socialists have increasingly engaged in petty bickering. Rather than providing a sensible counterweight to the ideological insanity of the far Right, the Left is parroting similar calls by Steve Bannon: that the system must be destroyed. Leaving aside the legitimate concern about how dysfunctional North America’s constitutional systems have become, what the left plans to replace that system with is unclear.

Consequently it is not difficult for the astute observer to see that the prevailing political mess may only be addressed after some kind of cataclysmic event. During the early part of the twentieth century, two world wars were required to defeat the socioeconomic crisis that abstract authoritarian ideology had inflicted on the world. That ideology has returned, the lessons conveniently forgotten by the body politic.

War may not be the only event that triggers a radical rethink of the current malaise. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina and the Bush Administration’s failure to address the crisis contributed to his party’s decimation in 2008. Contrast that with Federal assistance in 2012 under Obama to New Jersey in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy and conservative opposition to sending such aid.

In the words of the Canadian singer and poet Gordon Downie “An accident is sometimes the only way to work our way back from bad decisions.”

Another solution may be unfolding in the wake of Trump’s reactionary policies. Countering his decision to pull out of the Paris Accords, many American cities and states are pledging to uphold the Accords in spite of the Federal Government. With enough grassroots involvement, Trump’s lunatic presidency might end up leading to a true democracy for the first time in the history of the United States. A democracy without the hindrance of the Electoral College or gerrymandering.

However that same movement could also easily fall into a trap of competition between communities and in turn lead to civil strife and human suffering.

If that were to occur, it would prove a final victory of the neo-conservative movement.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND FURTHER READING:

BLACKWATER: THE RISE OF THE WORLD’S MOST POWERFUL MERCENARY ARMY BY JEREMY SCAHILL

THE DOUBTER’S COMPANION: A DICTIONARY OF AGGRESSIVE COMMONSENSE BY JOHN RALSTON SAUL

CRIME AS STRUCTURED ACTION; DOING MASCULINITY, RACE, CLASS, SEXUALITY AND CRIME BY JAMES W MESSERSCHMIDT

THE TURNER DIARIES BY WILLIAM LUTHER PIERCE

PRODUCTIVE CHRISTIANS IN AN AGE OF GUILT MANIPULATORS: A RESPONSE TO RONALD J SNIDER BY DAVID HAROLD CHILTON

THE MANY-HEADED HYDRA: THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF THE REVOLUTIONARY ATLANTIC BY PETER LINEBAUGH AND MARCUS REDIKER

argument over whether we can effectively populate the universe with ghosts of our own emotional and juvenile angst.

argument over whether we can effectively populate the universe with ghosts of our own emotional and juvenile angst.

). The book was waiting for me on the UAA Consortium Library cast-offs cart for the stated price of $.25 and, as I said, I could not (would not) resist.

). The book was waiting for me on the UAA Consortium Library cast-offs cart for the stated price of $.25 and, as I said, I could not (would not) resist.